Information Architecture: A Journey to the Heart of the User Experience

BY ITW Consulting

Web Design and Development

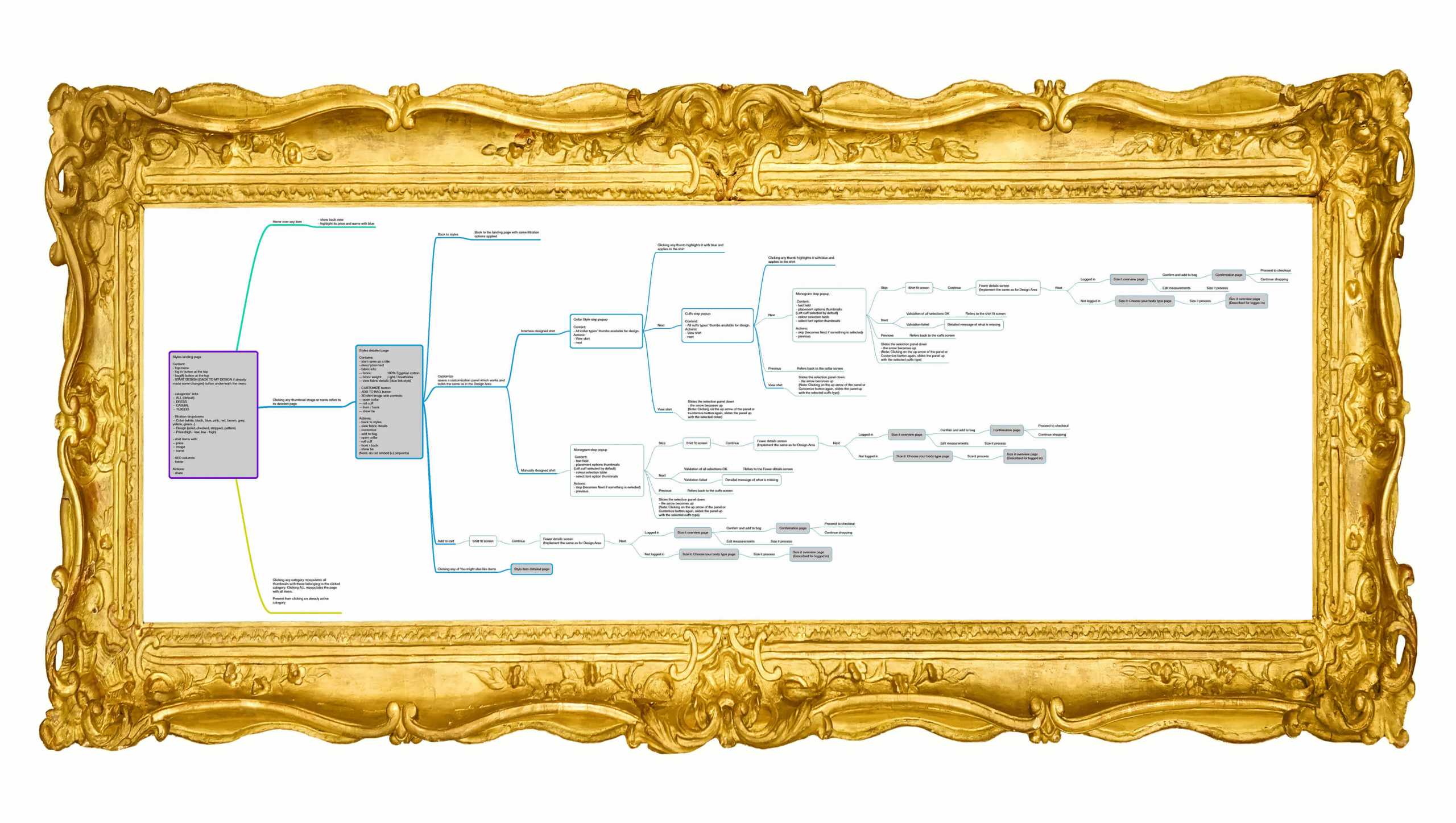

Without any sense of order a website, much like a home, is not a place that entices you to stick around for long. Chaos creates disorientation and frustration, and suddenly you can’t find the exit fast enough. In web design, information architecture functions much like a blueprint: by planning out every detail ahead of time, the architect ensures the most logical and intuitive functional flow possible when it comes time to build.

The hallmarks of effective information architecture:

- Intuitive navigation that makes getting around the website a breeze

- A well-defined hierarchy with a singular logic that governs the entire site

- A high conversion rate (when it happens, you’ll know)

- Connectivity between relevant pages

- Processes in place to avoid dead ends or unsatisfactory results (think half-completed transactions)

- A reaction to every action (for example an error message with instructions)

Information architecture and user experience design go hand in hand—sometimes even blending into each other within the same conversation. What’s important, though, is the emphasis on planning. While many websites share similar navigational schemes—not unlike the contention that all fiction can be boiled down to seven basic plots—web design companies actually face a huge array of decisions during the structuring of a site.

For the user, every click and every move deeper into the website is an investment. It’s the job of the information architect to make sure that those investments generate a return; in other words, users need to feel a sense of assurance about where they’re going and what they’ll find when clicking on a page or call to action. But before the information architecture can take form, it’s important to specify the target audience—the people most likely to use and benefit from the website.

Target audience: you talkin’ to me?

Each segment of web users carries a distinct set of experiences and expectations, which together provide a great starting place for any web design project. Although simple is always preferable to complex, certain categories of user can function just fine within a structure that challenges convention slightly (without, of course, forcing them outside their comfort zone). Information architects can never lose sight of the fact that users likely won’t bring the same level of web-savvy as them. What seems familiar to a web design expert can feel like a house of mirrors for someone else.

Confusion should never be on the menu

Entire books and companies tackle the subject of information architecture, so it should come as no surprise that descriptions and methodology vary. But, at the core of it all, information architecture is about planning—planning for the sake of usability, planning for the sake of an efficient web design process. Whether content dictates navigation or vice versa, the end goal remains remarkably consistent among all practitioners: to provide a foolproof user experience that also results in the completion of a desired action, for example a purchase or inquiry.

With this goal in mind, as well as the target audience, the information architect sets about establishing a hierarchy and navigation scheme. In rare cases an entire website will be condensed into a single page, but this is neither SEO-friendly (especially without distinct URLs to define content) nor conducive to expansion. More likely your website would require at least two distinct levels to deliver content effectively, and maybe more (with every additional level below the main navigation you run the risk of hurting usability—it becomes more difficult to orient oneself within the website as a whole and to understand the correlation between pieces of content).

One of the surest ways to confuse a web user is to establish a rule that applies 80 or 90% of the time. By breaking the logic of a particular section—or even an entire website—the information architect has created certain user expectations, only to contradict them later. Consistency is a hallmark of well-crafted information architecture. However, experienced web design companies understand that content rarely conforms to such standards on its own; it takes ingenuity, problem solving and a helpful mapping tool to tie everything together into a neat little package.

Ideally, a navigation menu will feature a healthy balance between choice and simplicity. Having too many top-level pages not only creates clutter in the main menu, it threatens to confuse the user by implementing an overly specific classification system. An exception here is news websites, which tend to use a commonly accepted series of categories; although this can also be combined with a dropdown navigation approach or a secondary menu, for easy entry into the site. Most web design projects, though, will feature more tightly focused subject matter—a series of products, a portfolio of work, a list of services.

Nomenclature: a pretentious way of introducing word choice

You will likely have noticed that most websites aren’t very adventurous when it comes to naming pages and sections—and for good reason. At its simplest level, good website design means instant connections. The learning curve should be miniscule and the getting-to-know-you period short and sweet. What information architects and others within the web design sphere call “taxonomy” is just a fancy way of talking about page naming. Convention, and extensive user experience testing and analytics, tells us that instant recognisability trumps abstract or clever wording in almost every case (exceptions being high-art websites or sites trying deliberately to break the mould).

Put another way: if success is what you crave, don’t get cute with your menu. Save the wit for lower-level pages, where your personality can really shine. Creativity is nice, but not at the expense of usability or, if you’re slinging products, conversion rates.

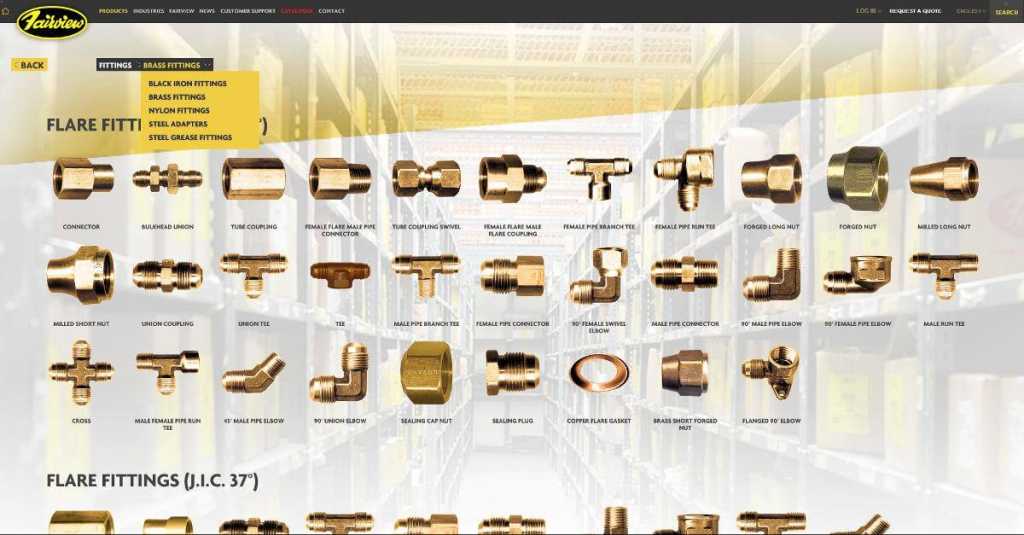

Ecommerce websites: a matter of dollars and sense

Although ecommerce websites don’t abide by a radically different set of rule from other sites, the reality is that online shoppers have become accustomed to doing things a certain way. Information architecture gives valuable structure to the product browsing and purchasing processes, which lie at the heart of every ecommerce website. It defines, for example, how users will access certain products from the main menu; whether products are cross-listed among different categories; whether to include dropdowns to reduce the amount of clicks; what should happen in the event of a transaction error to avoid a missed opportunity for a sale; and many, many other processes.

Web analytics tools are invaluable for spotting trouble spots after site launch. The information architect can pre-empt a lot of issues early in the web design process, but few ecommerce sites are flawless right out of the gate. Refinement is an ongoing process, especially with so much riding on the site’s ability to generate steady sales. It could be as simple as modifying the user interface or rewording the call to action, and with a well-thought-out information architecture it likely won’t be anything more significant than that.

You may also hear the term “functional flow” mentioned within the discussion on usability or information architecture. Functional flow as a philosophy is well known beyond the world of web design, but here it has become synonymous with user experience; in other words, the degree of ease with which users progress through a website. The paradox of good website design is its inconspicuousness—seamless experiences really don’t call attention to themselves, and that means a successful information architect shares a lot in common with the catcher of a baseball team. In addition to dictating the flow of action and always looking at least a few steps ahead, both are at their best when no one notices them.